▲Ted Alling discusses Dynamo, a new accelerator program for logistics, supply chain, and transportation startups.

— Photo courtesy of the Chattnooga Chamber of Commerce

In 2017, Fortune magazine called Chattanooga “One of America’s Most Startup-Friendly Cities.” Though some might balk at the suggestion that a mid-sized city in the Southeast could be on par with the Bostons and San Diegos of the innovation world, it’s not a surprising designation to people who know Chattanooga. The city’s rich environment of entrepreneurial resources—combined with its relatively low cost of living and reputation as a recreational and social hotspot—make it the ideal place for people looking to build something awesome.

By many outside accounts of Chattanooga’s innovation story, the launch of the Gig was the city’s first step in becoming a startup-friendly community. However, several local individuals and organizations began laying the groundwork well before and alongside the inception of the nation’s most advanced smart grid.

One of the earliest organizations to recruit creatives and entrepreneurs to Chattanooga, CreateHere partnered with the city’s foundations to incentivize individuals to relocate to Chattanooga and create something great. Started in 2007, the organization helped fledgling businesses set up operations in Chattanooga’s Southside and provided funding for artists to replenish the creative spirit in the city. Today, CreateHere no longer exists, but an off-shoot of the organization, the Company Lab (CO.LAB), carries on its work.

Created to address what many called a lull in Chattanooga’s entrepreneurial landscape, CO.LAB launched in 2010 as a support organization for local startup companies, offering mentoring, networking, and better access to funding all in one place.

“The reason Company Lab needs to exist and the reason resource centers like that need to exist, at this stage in the ecosystem, is this is not the type of work that school necessarily prepares you for,” says Jack Studer, Executive Director at CO.LAB. “I know we have entrepreneurship programs in schools, and that’s great, but they’re all designed to get people interested and to give them the very basic skills.”

CO.LAB does this through a variety of programming, as well as events. CO.STARTERS is a nine-week program designed to introduce aspiring entrepreneurs to the basics of starting and establishing a business. For companies further along in their development and that possess potential for high growth, CO.LAB Accelerator is a mentor-based program whose goal is to help startups stabilize their companies and become ready to seek investments. In addition, the organization hosts events including GIGTANK 365, 48Hour Launch, Will This Float?, and myriad other accelerator and pitch opportunities.

Much like the sector that it serves, Studer says, CO.LAB has to continually be on the edge of what’s next. By becoming too comfortable with the “We always do this” mentality, it’s easy to shift away from being an innovator.

“If you’re innovating, you’re by definition doing something that’s never been done before or doing something in a way that’s never been done before, Studer says. “If you’re an expert, how much can you innovate? … Company Lab has to constantly reinvent itself. It just has to. You can’t be in the innovation business or the innovation support business and not constantly be reinventing yourself.”

The staff at CO.LAB provide resources to the city’s entrepreneurs through a host of programs and events, including 48Hour Launch, CO.STARTERS, and GIGTANK.

-photo by Stephanie Norwood

A New Model for the Incubator

In 2010, Barry Large, Ted Alling, and Allan Davis were young millionaires in their 30s, enjoying great success with their freight-handling company, Access America. But they added a new and different venture when the three founded Lamp Post Group. It was a new business incubator, a network with both capital and connections to give other creative entrepreneurs a leg up, by offering capital and logistical and tech support for the most promising startups.

Large, Alling, Davis and company saw a need for a whole different approach, a for-profit incubator that might benefit not only from their accumulated capital–currently they have access to about $50 million in reserve for LPG and its projects, with an additional $18 million raised recently for the Dynamo Fund–but from their experience.

Large explains the business plan of LPG in the simplest terms: “What we do is try to find founders. A founder is any person or group of people who comes together to try to start something. We go out and seek those folks, figure out if it makes sense for us to invest in them with our time.”

He sees a pattern in businesses that tend to work. And he tends to suspect that the businesses that tend to work are the ones that resemble the big success he’s most familiar with.

“We tend to not invest in solo entrepreneurs,” Large says. “We like a team–like a three-piece team. It’s what we know. With three, you have a tiebreaker in a vote. In the best teams, you have complementary skill sets, and not a lot of redundancy. Every team needs a Type A, someone who’s aggressive, bordering on delusional, who believes that this company, against all odds, is going to be successful. You have to have that belief bordering on delusion, to be successful. For our story, that person probably is Ted, our extrovert recruiter. But you also need that counterbalance, that pragmatism.”

They enlisted a few other partners. One was Miller Welborn, a logistics consultant but also a well-connected banker, and the only fellow over 40 in the group.

Another was Weston Wamp, a young University of Tennessee grad who seemed headed for politics. He ran a close race for the Republican nomination for the Congressional seat once held by his father, Zack Wamp, who had represented Chattanooga’s district in Washington for 16 years. He was excited by the Lamp Post prospect.

When Atlantic Monthly profiled LPG in 2011–the article was called “The Unusual Startup Incubator that Could Exist Only in Chattanooga”–they emphasized the fact that these were creative people swimming against the coastal grain of New York and Silicon Valley, in that these folks–some of them, anyway–were politically conservative.

Large calls Chattanooga a perfect start-up community. “Chattanooga is a nice mid-sized city,” he says. By the last census, the city was home to 168,000. “It feels even smaller than that. But it’s smaller, more nimble.” People know each other, and you can see when your efforts make a difference.

It would seem their efforts have paid off. During the past several years, Chattanooga has experienced a swell in the number of new enterprises starting up in the city, with Hamilton County leading the state in new business formations in 2017. According to the Tennessee Secretary of State office, Chattanooga saw a 32.2 percent increase in year-over-year new business filings between 2016 and 2017.

Alling adds, “We want to make Chattanooga the best place in the world to start a business.”

— Photo courtesy of the Chattnooga Chamber of Commerce

Building on a Logistics Legacy

Alling, Large and Davis started LPG after selling their logistics company, Access America Transport, to freight broker Coyote Logistics, Inc. in 2014. (A year later, UPS bought Coyote.) But they were hardly in a mood to quit the logistics business.

For their next project, LPG borrowed a booster phrase from Chattanooga’s deep industrial history: Dynamo.

This time, the old word would apply to a new accelerator for supply-chain technology startups, to bring fresh tech talent to the freight business. It would, in Lamp Post’s words, “bring capital and mentorship to tenacious and unconventional founders operating in the logistics, supply chain, and transportation industries.”

One of the disappointments of the Internet is how much of this sudden new access to electronic information, and faster and more complex ways to use it, is squandered on the trivial, the superficial, the silly. With Dynamo, Lamp Post hoped to bring the latest and most dynamic tech trends to something more substantial than social media. And with a strong logistics history, Chattanooga seemed like an ideal launching pad.

For many companies, particularly those with a physical product, geography plays an important role in selecting an operational home base. In these cases, smart logistics can literally open pathways to customers, suppliers, and potential partners. Luckily for Chattanooga, the city is located in what many people call a logistical sweet spot, sitting at the crossroads of three major interstate systems—I-75, I-24, and I-59—on a river, and with easy rail access. With the addition of the Gig, Chattanooga is at the next frontier in logistics infrastructure.

“Logistics is kind of part of our DNA,” says Charles Wood, Vice President of Economic Development at the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce. “Before Europeans ever settled the U.S., Chattanooga was a place where, because of the river, trade happened. For companies, that access to their customer base and to be able to move product is probably the single biggest competitive advantage that we have.”

A three-month accelerator program, Dynamo drew the attention of the Wall Street Journal, which in March 2016, described LPG’s Dynamo initiative with a comparison Tennesseans aren’t used to hearing. It was, the Journal said, a “Silicon-Valley style accelerator for supply-chain technology startups.”

“More than anything, we look for relentless entrepreneurs,” says Wamp. “Recently, through the creation of Dynamo, we have begun to focus on the transportation and logistics sectors. The goal at the outset of the Dynamo era of Lamp Post,” Wamp says, “is to make Chattanooga the best place in the U.S. to start or fund a logistics or transportation tech company.”

Dynamo is structured as three, four-week phases, each focusing on a different aspect of company building and refining. Mentored by an impressive mix of executives and entrepreneurs from all across the country—and companies ranging from GE to Chattanooga startup Skuid—Dynamo participants get an accelerator experience tailored to their unique needs and potential. Ten companies completed the inaugural Dynamo accelerator in October 2016, and several have since moved their operations to Chattanooga.

-photo by Doug Barnette

Hatching Successful Businesses

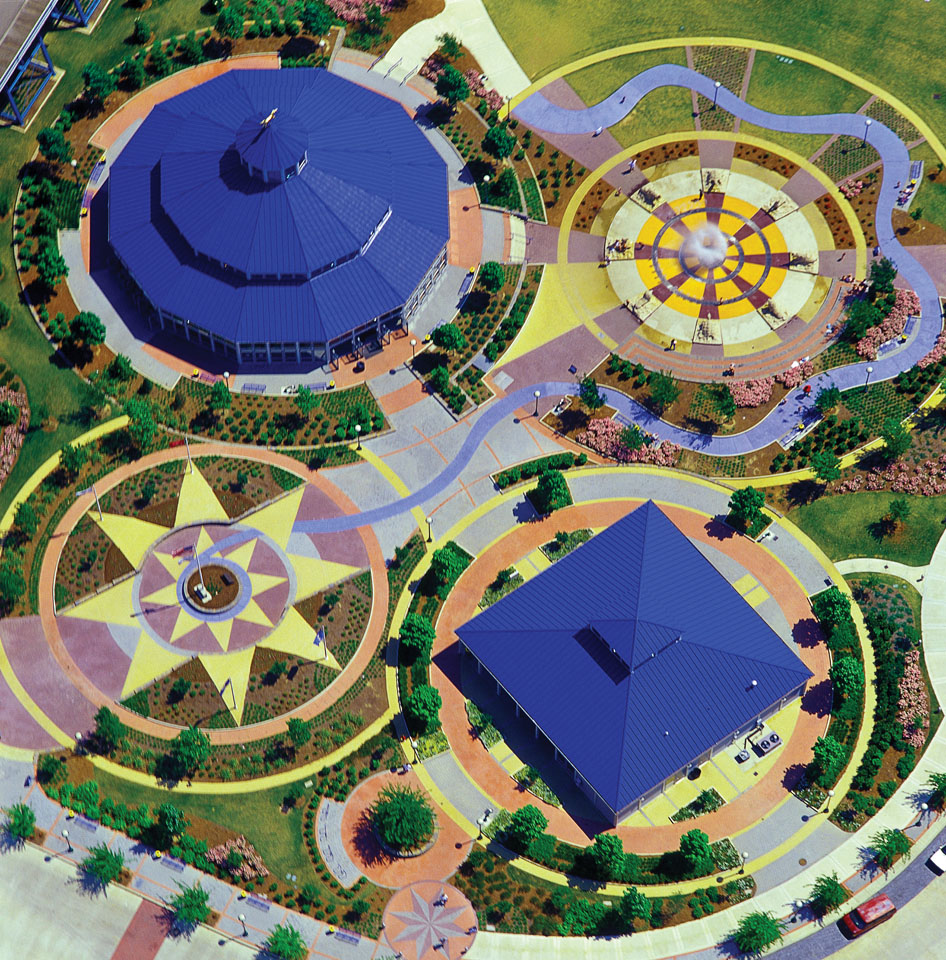

Conceived in the 1980s inside a renovated former 3M factory, the Hamilton County Business Development Center (BDC) is on the NorthShore of town and houses a trio of programming that forms an entrepreneurial ecosystem for new businesses. Known most notably known for its INCubator program, the BDC is home to one of the largest business incubators in America, helping more than 560 businesses “hatch” since the center’s inception.

The INCubator is operated by the Chattanooga Chamber and offers startups low-cost operating space within the BDC’s 127,000-square-foot facility. With spaces ranging from 100-square-foot offices to 5,000-square-foot manufacturing facilities, the INCubator has attracted a diverse roster of clients—from a handheld sensor platform, to military tactical weapons, to the world’s largest freeform 3D printing platform.

Startups applying for the program must present a detailed business plan and have a relationship with a mentor from the Tennessee Small Business Development Center (TSBDC), among other requirements. Companies that are accepted into the program can take advantage of subsidized rent for three years and also have access to large conference rooms and meeting spaces within the BDC.

According to Kathryn Menchetti, Director of Small Business and Entrepreneurship at the Chamber, the BDC, unlike many incubator-type spaces for startups in the city, offers manufacturing and technology clients a more industrial setting for product creation, complete with high ceilings and concrete floors. The BDC also recently welcomed a suite of labs—accessible to anyone—that will allow people to utilize features such as virtual reality equipment, geological testing resources, and a makerspace.

In the program’s early days, technology was not a highly represented field in the BDC, Menchetti says. When she began working there 12 years ago, manufacturing, lifestyle, and hobby companies dominated the makeup of the incubator program. Today, however, she says there has been a dramatic shift toward tech startups.

“We’re looking for companies that are going to scale,” Menchetti explains. “The landscape is different now—there are so many startups in the Chattanooga area that we’ve had to bob and weave. And we understand that the tech companies are going to create jobs that are going to be much higher paying. There’s just such a demand for space and for companies that need what we have.”

In addition to the space and financial benefits, companies in the INCubator program utilize counseling and community classes offered through the Chattanooga branch of the TSBDC, which also occupies the BDC. A third anchor tenant, ChaTech is a technology resource for tenants and the business community at large. Hosting events and programs such as an annual developers summit and monthly hot-topic forums, ChaTech rounds out the BDC’s ecosystem that supports early innovators.

According to the National Business Incubation Association, startups that build their businesses inside an incubator have a five-year success rate of 87 percent, compared to 44 percent among non-incubated companies. At the Business Development Center, that figure is 92 percent.

Menchetti attributes the INCubator’s success to not only the program’s stringent vetting process but also the supportive entrepreneurial culture of the city.

“I think it has a lot to do with our ecosystem that we have in Chattanooga,” she says. “The community feel of success and collaboration is wonderful, and then that spills out into this fabulous community that we have, which is supported with the Innovation District, and CO.LAB, and Lamp Post Group and everybody else that is singing our favorite song: ‘startup is cool.’ … It takes a village, and we sure have got a good one.”