-photo by Stephanie Norwood

The Chattanooga Renaissance that found its roots in planning initiatives like Vision 2000 and the Tennessee Riverfront project brought some of the landmark recreation and tourist amenities the city enjoys today. Perhaps more importantly though, it ushered in a lasting standard for making great things happen, anchored by a spirit of collaboration across diverse sectors: The Chattanooga Way.

When Chattanooga native Jack Studer returned to his hometown, he had just sold his document security software company and was looking to take a much-needed break from consulting work, which was taking him all over the world. But what was supposed to be a lazy summer spent by the lake presented a series of connections that would ultimately lead to Studer remaining in Chattanooga and becoming a permanent fixture in its entrepreneurial ecosystem.

After meeting David Belitz and Charlie Brock, the trio started the Chattanooga Renaissance Fund (CRF), along with Roddy Bailey, Miller Welborn, and Stephen Culp. The “first organized capital in a long time in town,” Studer says, the angel capital fund helped fill the void in financial support available to businesses in their infancy. In addition to receiving investments from CRF’s $7.6 million fund, startup’s leaders engage with the fund’s partners through mentoring and coaching.

CRF’s portfolio includes 30-plus companies, from Chattanooga-based outdoors review site RootsRated, to INCubator success story Collider, which uses manufacturing-grade materials in 3D printing production. While its investments are not exclusive to Chattanooga, CRF concentrates most of its work in the Gig City and nearby surrounding metros, including Nashville and Knoxville.

CO.LAB Executive Director Jack Studer

-photo by Stephanie Norwood

The goal of CRF, Studer says, is to grow not only successful businesses but also successful communities. The fund has been especially involved in cultivating an innovator-friendly environment in Chattanooga that didn’t exist when it first launched.

“CO.LAB, CRF, and Lamp Post—those were sort of the first three big things on the scene,” says Studer, who is also the Executive Director at CO.LAB. “All three of those not only had to invest capital—or resources in CO.LAB’s perspective—they had to build infrastructure as well. So, CRF didn’t just invest in companies, we also invested in the community. Some of our money had to go to sponsorships and marketing and doing things that wouldn’t necessarily drive a profit, but we had to get the environment built up.”

Studer references a 1986 The Chattanooga Times interview with Jack Lupton that he says gets passed around once or twice a year among Chattanooga’s entrepreneur community, many of whom were not yet born or were toddlers at the time of its printing. In it, Lupton unabashedly defends his investments in Chattanooga projects against critics who suspected ulterior motives, saying: “I’ve got not one thing to gain out of this except a better place for you and your kids and their kids to live.”

That sentiment has stuck with Studer and several other successful Chattanooga entrepreneurs, who view community reinvestment as a civic calling.

“We know that the city we love exists because of someone like that; the stuff that he did, the seeds he planted. We all share a little bit of that,” he says. “The cool thing, I think, about this generation is, right now, we’re not a community with one benefactor. There’s no one guy or girl driving this. There are a lot of us, and we’re all driving it—and that’s how we’re wired.”

When it comes to entrepreneurs supporting Chattanooga’s development, perhaps the most recognizable example is Lamp Post Group.

A Light in the Night

Kim White, president and CEO of the River City Company, first encountered the founders of Lamp Post Group when they were with Access America, and contemplating moving their headquarters downtown. Her organization was able to help get Lamp Post started. She’s been watching their progress with wonder ever since.

She remarks that Lamp Post arrived just as a generation of transformative philanthropists were dying off and were able to carry the city’s banner forward.

“What a great example,” she says. “Ted and Allan and Barry coming in, bringing us a different kind of philanthropy.”

The venture incubator not only provides investment and mentorship to its companies, but also has expanded into real estate with Lamp Post Properties. What started with the purchase of the second floor of the Loveman’s Building to house Lamp Post operations organically grew into a full-fledged effort to rehabilitate downtown, focusing on some of Chattanooga’s most historic buildings. Lamp Post Properties officially launched in 2016 and has acquired six historic buildings which house or will house some of the city’s most exciting companies, living spaces, shops, and restaurants.

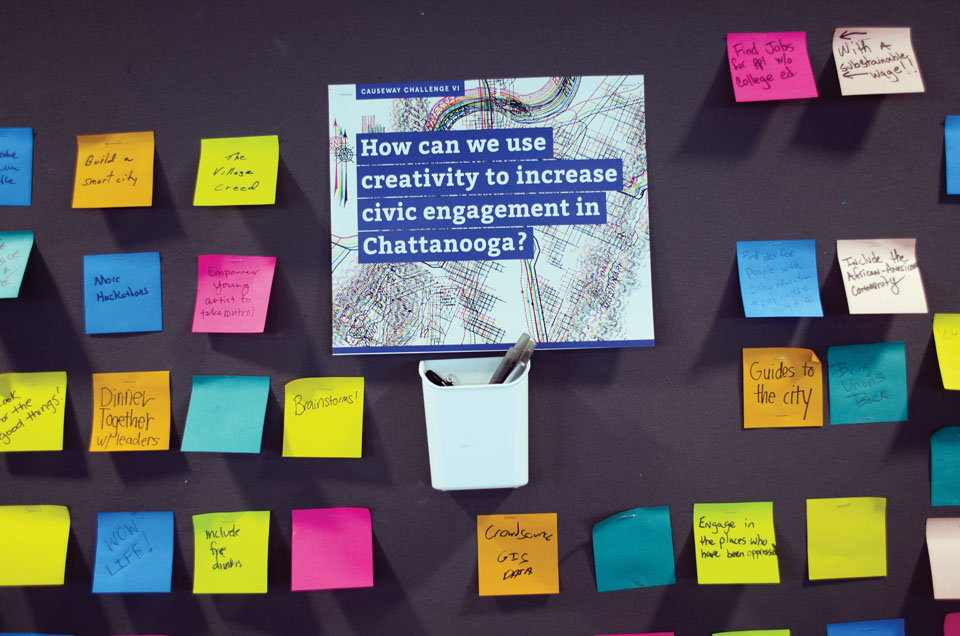

Approaching innovation from a social perspective, Causeway uses principles of entrepreneurship to solve community and civic issues.

-photo by Stephanie Norwood

Although Lamp Post is a private, for-profit company, partner Weston Wamp makes it sound like a municipal mission.

“For Chattanooga to get where it’s going, it’s critical for the downtown area to fully recover,” he says. “The vibrancy of downtown is going to be recreated by people living and working downtown, so it was a priority that we make a big investment in the middle of the city.”

But not all investments are monetary. Sometimes, stepping beyond its role as a new-business incubator for Chattanooga, Lamp Post makes a strong impression on a few existing national ones.

In 2013, Ted Alling invited Gary Vaynerchuk, author, winemaker, and hyperactive entrepreneur who has been an investor and advisor to some of the century’s most notable startups, including Facebook, Uber and Twitter. He visited the Lamp Post offices in the Loveman’s Building and liked what he saw, of the company and apparently also of Chattanooga. The following year, he returned to give a memorable talk about possibilities. By then, he had started his own social-media-oriented advertising company, VaynerMedia. Originally, VaynerMedia had three national offices—one in Manhattan, one in Los Angeles, and one in San Francisco. In 2015, Vaynerchuk opened this fourth one inside of the Mayfield Annex, a Lamp Post Properties building.

“A private company went out and recruited another private company to come and set up an office in town … just to bring a cool company in town to have another cool company here in town,” says Studer, who was a founding partner at Lamp Post Group before assuming his current role at CO.LAB. “That’s pretty forward thinking.”

Lamp Post’s role in VaynerMedia’s expansion to Chattanooga is just one example of what Studer calls “hybrid bottom lines.”

“It’s not just ‘How can we maximize how much money we make?’ but its ‘How can we create a more fertile ground for the future?’,” he says. “We’re [all] investing today for something that may not pay off for 10 years. And you just don’t see a lot of investors looking at it from that point of view.”

“The great thing about Chattanooga is its nonprofits… are pretty well aligned, For the last 15 years, we’ve had multiple mayors, but each has been a cheerleader, has done what they could to facilitate business.”

—Barry Large

photo by Stephanie Norwood

The Long View

When talking about Chattanooga’s new generation of leaders driving the economic development and renewal of the city, Ron Littlefield, like many, cannot help but observe the youth factor that has played such a large role in the philanthropy of today.

“As a city planner, I told folks I lost interest in long-term plans when I turned 50—I was only interested in things I could do in the next 5 or 10 years, or 20 at the most,” Littlefield says with a chuckle. “Young people are key because they have much more extended horizons; they’re thinking in longer terms.”

Indeed, people under the age of 40—many of them younger than 30—were responsible for much of Chattanooga’s startup activity in the last decade. From the leaders of Lamp Post Group, who founded Access America in their mid-20s, to CO.LAB founder Sheldon Grizzle, who was 27 at the time of the accelerator’s inception, young people were at the forefront of Chattanooga’s innovation movement long before the arrival of the Gig. And curiously enough, the more established regime of city leaders is welcoming them with open arms.

“The foundations and then the civic side, with the mayors—they were very adept and very aware of, ‘Yeah, this is risky. We’re inviting the young people who don’t know what they’re doing to do stuff,’” Studer says. “But when you get them in the right place, young people can actually take a really, really long view because they’re going to be around for it. We get to live in this place for the next 20 years—good or bad.”

Reorganized in 2014 as a result of the Chattanooga Forward initiative, The Enterprise Center is a public-private partnership working to establish the city as a hub for innovation and technology.

-photo by Stephanie Norwood

A Foundation in Foundations

Though private enterprise has played a major role in Chattanooga’s latest Renaissance as a technology and innovation hub, support from the city’s major foundations remains a pillar of the Chattanooga Way. However, much like in the past, the foundations are shifting their focus along with the changing needs of the city and region.

Established in 1944 by Benjamin Franklin Thomas’ heir to the Coca-Cola Bottling Company, George Thomas Hunter (for whom the city’s Hunter Museum of American Art is named), Benwood Foundation started with the mission to “promote religious, charitable, scientific, literary, and educational activities for the advancement or well being of mankind.” That mission has changed over the years, but its main beneficiary—Chattanooga—has not.

Focused today on supporting the “people and projects that make Chattanooga a great city,” Benwood has filtered its support through the lens of four focus areas: Place, Culture, Talent, and Competitive Advantage.

“What a great example, Ted and Allan and Barry coming in, bringing us a different kind of philanthropy.”

—Kim White, CEO

River City Company

— Photo by Karen Culp Photography

Together with the Lyndhurst Foundation, Benwood sponsors much of the activity that is driving the city’s economic development, including CO.LAB’s GIGTANK and 48Hour Launch. The foundation is also one of the driving forces behind Chattanooga 2.0. One of the annual events that showcases all four of Benwood’s philanthropic tracks is Startup Week Chattanooga. Launched in 2014, the weeklong series of networking and social events, classes, panels, workshops, and demo showcases shines the spotlight on what is happening in Chattanooga’s startup community.

In 2016, the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation issued a report hailing Chattanooga’s “layered entrepreneurial ecosystem,” which has evolved from years of public-private partnerships. By the 21st century, Kauffman observed, it grew to include foundations and other funding groups, entrepreneurial-support organizations, traditional public entities like the mayor’s office and public utilities, and the Innovation District.

“The great thing about Chattanooga is its nonprofits, etc., its city, county, chamber, are pretty well aligned,” says Barry Large, of Lamp Post. “For the last 15 years, we’ve had multiple mayors, but each has been a cheerleader, has done what they could to facilitate business.”

The Kauffman report notes that Chattanooga’s model of diverse entrepreneurial support has become almost a point of “civic pride” among Chattanoogans. From civic leaders to stay-at-home moms, residents who have no direct ties to the startup community attend business events and gatherings because entrepreneurship is quickly becoming a tie that binds the city together.

The study’s authors write: “Creating an environment where entrepreneurs are not just nurtured and encouraged, but celebrated, helps current entrepreneurs and primes the ecosystem to better support future entrepreneurs.”